Getting more freight onto rail in Aotearoa New Zealand

Shifting more freight from trucks to trains reduces road congestion, improves safety, lowers maintenance costs, cuts emissions, reduces pollution, decreases fuel dependency, supports renewable energy, and revitalises passenger rail for better mobility. It's a no-brainer, so why aren't we doing it.

POLICYCLIMATE CHANGEPLANNINGFREIGHTFERRIESINFRASTRUCTUREINVESTMENT

Paul Callister

4/26/20257 min read

Imagine a transport policy that would reduce congestion on roads; make them safer; reduce highway damage and maintenance costs; lessen emissions; lead to greater use of valuable renewable energy; reduce pollution, including from tyre wear and particulates; lower our dependency on imported fuels; and underpin the revival of inter-regional passenger rail, thus giving kiwis and tourists more mobility options.

Imagine a New Zealand transport policy statement beginning with:

“The Paris Agreement goal requires ‘holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels’ (UNFCCC, 2015). Consequently, countries are required to make ambitious efforts to decarbonize their economies. Reaching this objective, calls for the implementation of far-reaching structural and technological transformations in all main emitting economic sectors, including freight transport.”

Unfortunately, no amount of imagining will conjure up such a statement as these are not to be found within any recent government transport policy documents. This includes the Government Policy Statement on Transport, which drives transport funding decisions.

One of the first major policy decisions of the new coalition government was to cancel the Cook Strait IREX ferry project. This resulted in high levels of uncertainty about the long-term viability of much of the rail network, particularly in the South Island. So, the recent decision to buy rail enabled ferries is especially welcome. However, this is just a starting point towards helping protect our current low carbon emissions transport infrastructure in the form of our main trunk railway line, which delivers freight between Auckland, Christchurch, Dunedin and Invercargill.

It is clear that our rail network could do much better to support emissions reductions. Also, a thriving rail freight system offers many other benefits.

An integrated strategy to reduce transport emissions

A recent research paper, from which the above climate change quote is taken, examines ways of reducing transport emissions by focussing on the role of the freight sector. Based on an international literature review, it suggests four important starting points:

1. Reduce freight transport demand and distances through the spatial reorganization of supply chains, digitalization, and the structural distribution system;

2. Maximize the efficient use of rail and waterways freight transport by increasing high-volume freight flows and facilitating intermodality;

3. Limit the energy consumption of vehicles through technology and behaviour;

4. Switch to low-carbon vehicles and energy carriers.

The research paper warns against siloed thinking, especially in relation to technological innovations within particular sectors. There needs to be a system wide lens applied to transport solutions.

This can be seen in discussions of decarbonising long-distance freight. For decarbonisation of trucking, hydrogen powered trucks have been pitted against battery powered ones, although the hydrogen bubble is rapidly bursting.

In relation to battery trucks, a debate remains about battery swaps versus rapid charging enroute. But, using a wider lens, there is the superior option of moving freight from trucks onto trains, with more emission and energy benefits if the trains are electric. Even just the simple labour productivity gains of switching to trains can be significant: one train driver for 50 containers versus 25 truck drivers if all the trucks have trailers.

Beware of powerful private sector lobbyists

This siloed thinking is encouraged by many factors, but lobbyists play a major part. Work by Otago University researcher Dr Alice Miller documents the power of what she terms New Zealand's "road lobby". Individually, the lobbyists include those who advocate on behalf of: fossil fuel companies, vehicle and vehicle parts sellers, trucking companies, and groups purporting to represent individual motorists. Collectively, these groups are well-funded and wield power across all levels of society, including government. Although not covered by the study, the companies who build and maintain roads also have a huge, vested interest in policy decisions.

In the other corner is KiwiRail. It is hampered in its own lobbying power by being a government owned enterprise, operating under the regulatory requirements of the NZ State Owned Enterprises Act.

The Future is Rail supports the campaign that has just been launched to rein in lobbying.

How unfair capital funding practises have distorted modal share

But even without current lobbying, the system is already stacked against rail freight, including the years of underinvestment in rail infrastructure.

In New Zealand, most money goes to roads. These include a series of very expensive Roads of National Significance (RoNS). Over the last decade and a half, motorists and truckers have enjoyed substantial time savings and gains in competitive edge relative to other modes due to the RoNS projects. Yet many of these projects do not stack up on value for money analysis, even if they include so-called Wider Economic Benefits.

On these new roads who will drive the trucks? Our truck driver workforce is ageing, and the industry is increasingly likely to rely on migration. It is a tough job, with frequently long periods away from home and night driving, which often results in an unhealthy lifestyle of limited exercise, topped up with fast foods during short breaks.

Re-balancing long term funding to enable sustainable transport

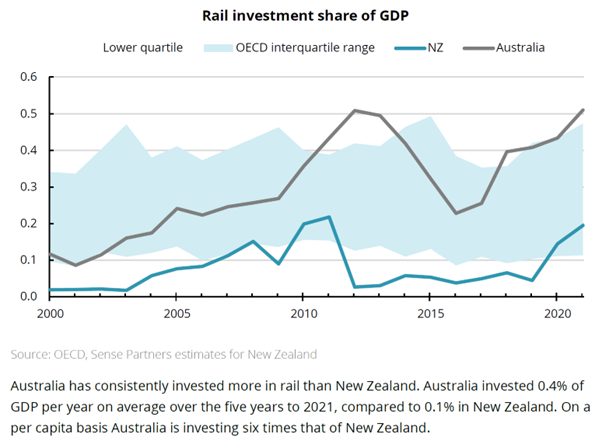

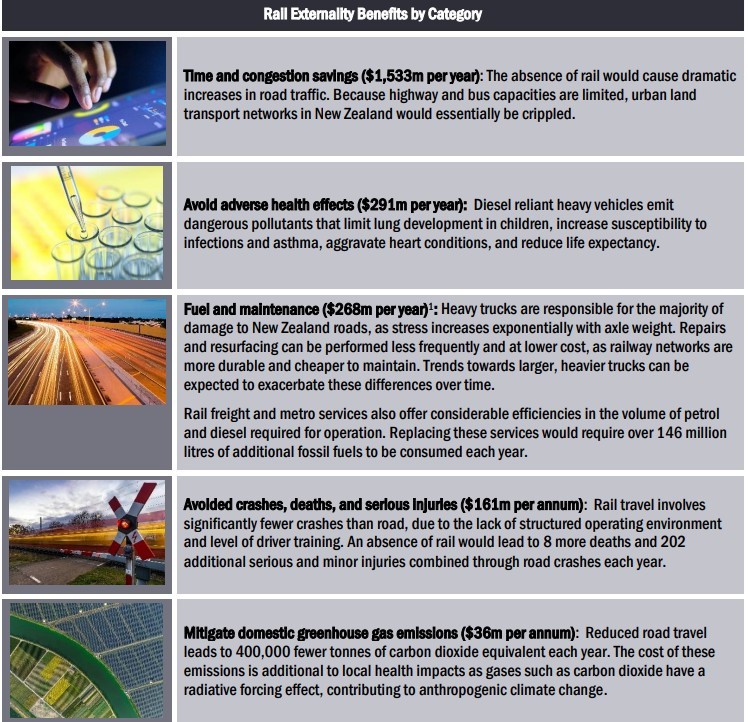

In contrast to many roading projects, the benefits of rail investments are clear, as shown by a recent study prepared for the Australasian Railway Association.

New Zealand’s new rail enabled ferries are an important part of rail investment. So too would be state-of-the-art rail/road freight hubs, such as the currently stalled Bunnythorpe freight depot.

Rail is on the cusp of a technological revolution. Robotics, AI, advanced signalling systems, satellite communication and tracking will all help run the railway network more efficiently and help maintain the infrastructure. Autonomous freight train operations and track maintenance technology promise to be game-changers. This will allow for “customer friendly”, smaller, nimble, and more frequent trains that are able to operate across a wider network, with greater access to individual industrial locations. If we invest now in infrastructure, we can reap the benefits for many decades to come.

The damage created by the current road pricing and regulatory regime

But it is road pricing that really forces freight onto trucks. Heavy trucks do not pay their full cost of damage to roads. A study commissioned by The Future is Rail shows this clearly.

This helps truckers undercut rail freight. For example, trucks pay the same Road User Charges (RUCs) whether they are on lightweight, high maintenance cost, rural roads or on heavy-duty high usage urban motorways.

A higher gross weight category of truck, officially designated in New Zealand as High Productivity Motor Vehicles (HPMVs), came into operation in 2010. HPMVs may have slightly increased freight haulage profit margins for truckers, and have definitely enabled the roading industry, as a whole, to benefit through the financing and servicing of a nationwide fleet of HPMVs.

However, the two biggest economic impacts of HPMVs have been to: (a) lower freight rates charged by all modes including rail and (b); generate an unanticipated level of damage to national highways, regional and rural roads. In summary, the outcome has been a transfer of costs from the private sector to national and local government to pay for the damaged roads.

In contrast, freight rail charges to customers may vary according to the underlying infrastructure maintenance cost and usage. Fewer trains on any given route mean that the fixed costs of the rail corridor get shared among fewer customers. Under the NZ State Owned Enterprises Act, Part 1, Section 4, Paragraph 1 (a), KiwiRail is required to be 'as profitable and efficient as comparable businesses that are not owned by the Crown'.

Collectively, this inhibits rail’s ability to respond to the competitive pressures generated by trucks.

If trucks paid their full cost of damage would this add to the ‘cost of living crisis’? It is probable that the goods carried by trucks would increase in price. But there is no free lunch. The damage has to be paid for somehow, it is just now that the cost is not so directly obvious to consumers, it is instead spread across ratepayers and taxpayers.

New sources of rail traffic that help the planet

There is clearly a need to get more existing freight onto rail. But what might be new sources of freight for rail? One is wood and wood products. Already, rail is an important carrier of logs. For example, log trains are loaded at KiwiRail’s Murupara rail siding, leaving the yard every four hours, six times a day, seven days a week.

But if wood is used as an industrial fuel or as a feedstock for producing liquid fuels then rail will be the most efficient way to transport the wood. Genesis is currently exploring using timber products to fuel the Huntly power station, with rail seen as a key way to move the wood and Air New Zealand has supported research into using wood as a feedstock for alternative aviation fuel. In the latter study, it was suggested that rail would be used to transport wood to a processing plant, then again used to transport the fuel to main airport supply networks.

Time for Change

The Future is Rail would like to see a number of policies implemented in relation to transport. These include:

1. All transport policies be guided by the need to quickly and dramatically reduce emissions.

2. Road users pay the full cost of using the roading network. This would include a range of policies, including weight of vehicles, cost of building and maintaining new and existing roads, perhaps through tolls, and congestion charging near urban areas, especially where there is a parallel rail corridor.

3. Government investment priorities be rebalanced, with less money going towards roads and more towards rail.

4. Policy development is supported that encourages reorganisation of logistics, hubs, and supply chains away from low-energy efficiency, ‘just-in-time’ delivery. Other initiatives to be considered that will impact New Zealand include the digitisation of manufacture and more sustainable global food production and distribution.

5. Efforts are made to reduce dependency on imported fossil fuels, with their long and increasingly uncertain supply chains, and replacing these with domestically produced renewable electricity or sustainable bio-fuel sources, where feasible, such as from forestry slash.

6. Lobbying be reined in. Politicians and government agencies need to question their balance of relationships with groups who have a private financial interest in road over rail. Currently, it seems that the balance of voices is not producing outcomes that are in the long-term public interest.

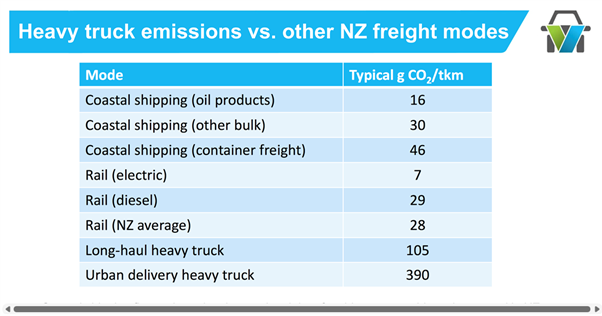

Graph is from the Ministry of Transport Study; Real world fuel economy of heavy trucks, prepared by Haobo Wang, Iain McGlinchy and Ralph Samuelson for the Transport Knowledge Conference 2019 (5 December)

Rail will continue to play an important role in New Zealand. This is due to the fundamentally low-friction characteristics of steel wheel on steel rail. In New Zealand’s topographically and geologically challenged landscape, the rail network stands out as a rich legacy of well-engineered corridors, with gentle gradients, that allow for energy efficient freight operations with a low carbon footprint.

Increasing the amount of freight carried by rail is a worthwhile goal on its own. But a thriving rail freight sector is needed to underpin the revival of long-distance passenger rail.